#i imagine New York City culture is different than New York culture

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

LA doesn't have the same culture as the rest of California. Regular Californian culture is probably closer to Nevadan or Arizonan culture.

#this is not a dig on la people and this is not a dig on the rest of the state either#i have lived in the mountains i have lived in the regular cities and i have lived in LA#i heavily prefer living in LA to anywhere else#my point is simply that#when out of state people think is Californian Culture TM#they are thinking of LA culture#I've never been i don't know if I'm right but#i imagine New York City culture is different than New York culture#i bet regular New York is more like Pennsylvania or New Jersey

1 note

·

View note

Text

I recently watched a YouTube video of a Ukrainian performance on “America’s Got Talent.” A friend sent me the link, promising it would amaze me – and it did. You can find the video by searching “Amazing holographic 4D cube show AGT.” However, when the show’s host, Howie Mandel, said, “America’s got love for the Ukraine,” I cringed. The phrase “the Ukraine” implies it’s a territory, not a sovereign country. It’s just Ukraine – the largest country in Europe, an important nation in its own right, and sadly, a place the world still knows too little about.

Ukraine is often branded as a place of corruption and gangsters, and Hollywood doesn’t help when it makes the villains Ukrainian. After living in Kyiv for years, I’ve experienced something very different. The country I know is filled with talented, hardworking, and warm people who possess an incredible sense of humor. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, too many people think Ukraine is nothing but a war zone.

I recently heard Mstyslav Chernov, the director of the Oscar-winning documentary “20 Days in Mariupol,” say that Americans often ask, “Is there more to Ukraine than the war?” I’ve had similar frustrating conversations abroad, with people asking, “Is that war still going on?”

Before the pandemic, I hosted many foreigners visiting Kyiv, often to explore IT opportunities. Questions like “Is it safe there?” or “Do they have the internet?” were common. Even more surprising are comments from the Ukrainian diaspora. In Canada, home to the largest Ukrainian community outside of Ukraine, some people who left decades ago have no idea how their country has advanced. “They have shopping malls in Kyiv?” or “Do they have electric cars?”

Yes, Ukraine faces challenges, and many people live on modest salaries. But there is a growing middle class, and the big cities capture imaginations. Every guest I hosted in Kyiv was blown away.

One misconception that always made me giggle is when people ask, “What will we eat there?” The food scene in Kyiv is incredible. There’s been an explosion of amazing restaurants, and dining out here can compete with New York or London any day. Even during the war, new places are opening, and the food is phenomenal. If you want to have a laugh, stand-up comedy clubs are popular – even in English. Where there’s laughter, there’s hope.

I had a friend from California visit twice, and when he returned to Los Angeles, people teased him, asking if he’d visited the land of Borat. He said Ukrainians are just like people in California – trying to build businesses, raise families, and live their lives. That’s the thing: Ukraine is not some backward nation that craves war.

Before the full-scale invasion, Kyiv was on track to become Europe’s next hotspot, and I’d have bet anything on that happening. This brutal war has set everything back. Ukraine is not about war. It’s about modernity, freedom, and new culture. It’s a country brimming with energy.

Ukraine has suffered from a poor reputation for as long as I can remember. I first discovered Kyiv nearly 17 years ago, and I’ve been saying ever since that Ukraine needs to work on its brand. Of course, now that we’re in the third year of the full-scale invasion, things are different. Air raid sirens can go off at any time, and it can be scary when Ukrainian air defenses shoot down drones and missiles. During those moments, you head to the bomb shelter. But life continues.

One of the biggest misconceptions about Ukraine is that everyone here is poor and miserable. Most people don’t have easy lives, and yes, poverty exists, but that’s true in many places. I’m originally from South Africa, where poverty exists on a different scale. In Ukraine, no one lives in shantytowns. When millions of Ukrainians fled across the borders, the European host nations were often surprised to see modern cars, fashionable clothes, and the latest smartphones. It’s a high-tech nation, and the level of online convenience here would surprise any foreigner.

There’s also a wave of innovation happening. Ukraine is poised to become a global leader in military drone technology. Artists are creating, entrepreneurs are developing cool tech, new restaurants are opening, and foreign investors are exploring opportunities. Ukraine is a miracle. Even as hypersonic missiles and kamikaze drones rain down across the country, many have decided to stay, continuing their lives, albeit in a very different way. The economy needs to keep running. Life needs to go on to keep the wheels turning.

Many passionate, dedicated people are working on projects to benefit and support Ukraine. Some have been involved long before the full-scale invasion, driven by a deep belief in the country and its people. Since 2018, I’ve been part of a team of artists — Ukrainian and international — creating a storytelling film project that captures life in modern Kyiv. “We Are Ukraine” is a story about extraordinary people in an extraordinary time — people who have chosen to continue to work, live, get married, have children, and laugh, against all odds. It’s not a war story, a story about death and demise. It’s a story about life, a love letter to Kyiv, which shows us what the world would miss out on if Kyiv would cease to exist.

Freedom, independence, and identity are the culmination of modern humanity, forged over centuries through struggle, creativity, and resilience. Everything else in civil society flows from these values. Russia’s war in Ukraine is a global wake-up call – a reminder that these values must be nurtured and protected. Ukrainians are showing that not only can they defend these values, but by continuing to live, laugh, and love, they are defying those who seek to destroy them.

youtube

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Midlife Crisis

Should I write this into a longer fic or leave it as is? I hope you guys like it and please leave your thoughts in the comments!

~*~*~*~

Steve didn’t know what to do with his life. It was a common thought he had on his shifts at Family Video. What was he doing? He of all people knew how short life could be and yet, he was wasting his own. Steve spent his weekdays working soul-draining double shifts just to sleep all weekend or work some more to make a meager $3.25 an hour. It was pathetic.

He didn’t have any goals or aspirations. His friends were making plans, trying to impact the world and make a difference. Dustin was taking a bunch of STEM classes so he could apply to MIT in a few years and work at NASA like some type of hotshot mathematical genius. Robin was applying for elite linguistics programs at colleges across the country to understand more cultures and ways of communicating. Even Eddie ‘repeated high school three times’ Munson had goals. He was traveling to different cities with the band, trying to make it big as Corroded Coffin.

Steve’s biggest goal was to get out of bed in the morning and stay alive for another day but he wasn’t even doing that very well. He needed something to be interested in, something to devote his life to and take pride in but he had no idea where to even start.

Steve was twenty years old and having a midlife crisis. He hadn’t even enjoyed any of the twenty years he’d been around and now it felt like he was too late to do anything about it. He was too old for college, too dumb to get in even if he wasn’t. He couldn’t get a good job without a degree or quality life experience and he couldn’t mention any of that thanks to a stack of NDA’s.

He needed something though. His parents were done with housing their deadbeat son who managed to disappoint them with anything he attempted. He was sick of his friends saying that they had to study or they’d end up like him. And he was sick and tired of being the only person he knew that had nothing going for him.

So one day, he decided to be spontaneous. He put in an application to the University of Illinois with an entrance essay about personal struggles, neglect, and self-doubt. He poured his heart and soul into that essay hoping against all odds that the admittance committee would look past his mediocre grades and would take a chance on the kid that struggled all by himself behind a smiling facade.

He forgot about the application until he got a letter in the mail from the university. He almost threw it away right then but decided to take a look just to reinforce what he already knew, no college would want him.

But they did. They congratulated him on his acceptance into their school in the fall and complimented the writing skills in his essay. They said they looked forward to having him join their program and mentioned that he would make a difference.

So Steve took them up on it. He kept the news to himself until it was time to leave and said his goodbyes to the Party on his way out of town. He was moving on so they could too. Steve wouldn’t be the one holding them back anymore. Then, he drove past the Leaving Hawkins sign without a backwards glance.

Years later, Steve thought back on his midlife crisis. He was just a stupid kid at the time that didn’t know all of the options he had at his disposal. Now, he was a world-renowned novelist with novels on the New York Times Bestseller list. He never would’ve seen himself becoming a writer but here he was, working his dream job.

He never would’ve seen himself dating Eddie ‘the freak’ Munson either but here they were, partnered since 1988, married since 2014, and touring the world together on the Corroded Coffin international tour.

Steve was having a crisis about a lot of things but everything turned out better than he ever could have imagined. He could’ve given up or accepted that he would never make a difference in the world or have a purpose in life. But instead, he took a chance and now he was living the best life that he could’ve ever dreamed of.

Permanent Tag List: @doubleb11 @nburkhardt @zerokrox-blog @newtstabber @i-less-than-three-you @carlyv @pyrohonk @straight4joekeery @conversesweetheart @estrellami-1 @suddenlyinlove @yikes-a-bee @swimmingbirdrunningrock @perseus-notjackson @anaibis @merricatty @maya-custodios-dionach @grtwdsmwhr @manda-panda-monium @lumoschild @goodolefashionedloverboi @mentallyundone @awkwardgravity1 @anzelsilver @jestyzesty @gregre369 @mysticcrownshipper @disasterlia @lillys-weird-world @messrs-weasley @gay-stranger-things @pnk-lemonades @coolestjoy30 @strangerthingfanfic @dangdirtydemons

#just a little crisis#he's fine#we're all fine#stranger things#steddie#fanfic#steve harrington#eddie munson#robin buckley#dustin henderson

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

We Would Not Be Here Without Akira Toriyama

I am sad and emotionally wrecked right now. We lost a legend that changed everything.

Akira Toriyama, who's famous for Dragon Ball and working on other properties like Dragon Quest, passed away at the age of 68 this March. It sucks because we're celebrating 40 years of Dragon Ball.

Dragon Ball Z was my gateway into anime fandom when I was a 5th grader literally 30+ years ago. Way before Toonami, I watched a Cantonese-dubbed episode of DBZ at a friend's place and became slowly hooked ever since then. Chinatown in New York City at the time was filled with Dragon Ball Z merchandise. Posters, toys, wall scrolls, video games, trading cards, etc. You name it, it was there. DBZ fandom wasn't as mainstream back in the early-to-mid '90s as it is now, but there was something. Especially for me.

I also remember my first time using the internet at a public library in 1999 and one of the first sites I visited was a GeoCities fan site about DBZ. That's how I found out about the original manga. My first manga purchase was Dragon Ball Z Volume 1 by VIZ Media in 2003 and it was a big-sized volume that was priced at $14.95 at the time.

Dragon Ball Z also got me closer to one of my younger cousins during the Toonami years and we formed a bond over anime since that time. I would play make-shift DBZ scenarios with him when he was little. I had Dragon Ball Z figures at the time. When I think about those days, I realize that it's those moments that count especially when kids are dealing with so much competitive stressors that don't encourage play.

I know everyone has their favorite Dragon Ball characters, but my favorite character ever is Vegeta. I wrote a whole bunch of articles about him through the years. One of my top posts ever was about growing up with Vegeta. And that was written 13 years ago.

At the time, I felt similar to Vegeta. I have this very lone wolf-ish disposition despite appearing friendly to a lot of people. I'll admit that I have softened a lot over the years. I don't have as much pride as Vegeta does as of late. But the thing about Vegeta lately is that he's a much different character than in the past. If you follow the Dragon Ball Super manga, you know what I'm talking about.

And then I realize I've grown up alongside Vegeta for 3 decades. It's surreal. Part of me feels like I haven't changed all that much like he has, but I have grown up in ways that I wouldn't have expected.

Which leads me to this - if it weren't for Dragon Ball Z, I wouldn't have gotten into anime. I wouldn't have gotten to explore other series beyond it. I wouldn't have gotten into manga. I wouldn't have met friends in fandom in my '20s. I wouldn't have fallen deep into the JRPG abyss. I wouldn't have gotten into Yakuza/Like a Dragon afterwards. I wouldn't have gotten into Japanese mahjong as a result of that. Dragon Ball Z started a chain effect that's still sending ripples to me to this day.

Akira Toriyama provided a introduction for me and everyone looking for something different into the world of Japanese pop culture. He is Cool Japan to me. Toriyama got so many people to see how wild, imaginative, fun, and inspiring Japanese pop culture media was. It's arguable that Toriyama had a much bigger impact on overseas fandom than Osamu Tezuka.

A lot of people involved in anime and manga would not be here if not for Toriyama. I want us to acknowledge that. I know I have. He was a game-changer or should I say, a world-changer for everything related to the perception of anime and manga globally.

Rest in peace and power, Toriyama-sensei! You will never, ever be forgotten!

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hiya! 😊 You're now a writer for the show. What three episode storylines are you gonna write? (In other words, what are you gonna make the boys do?)

ohm y god i literally have so many episode ideas but i'll try not to repeat any of the ones i've made posts about (except my first bullet bc im so passionate about it) so i'll give you my big list. most if not all will likely be something i DO end up writing about in my own story because ehehe i love making them do things

ones i think i've mentioned before:

a returning to minnesota chapter!! not for anything but nostalgia, getting to see the guy's favorite places, seeing their friends and families, bringing them back to realize how far they'd come. not so shy spon for my fic but i wrote a chapter like this last month and it's probably one of my favorite things i've written to date. it let me explore some of the boys' past, family dynamics, a little bit about Katie and agh i can't believe btr didn't capitalize on that at least once. ik its expensive to fund sets and hire new actors but idk i imagine it like an hour special where they could afford to shell out a bit more. idc when it happens, could be after they sign their record contract or the last episode or whatever :)

sketch comedy episode, something akin to saturday night live or so random

graduation! like you and i talked about lol i think it would be sweet

get me in the writers room stat:

originally i'd planned a "home alone lost in new york" like chapter for my story around thanksgiving where the boys are going to perform at the parade in town but they end up having their own adventure around the city beforehand. boyish antics, screaming gustavo, beautiful scenes, the works. i was just in too much of a slump to actually put it to paper :)

more tour-focused chapters (again, spon for my own fic lol) the episode in Canada was cute and the one on the bus was fun but idk there's just so many elements toward touring that i think they could've capitalized on; homesickness (for CA or MN), hardship of a go go go schedule, or fun things like being able to travel with your best friends and not ending up on the world's most wanted list lol. i know they tried really hard with this one so i don't blame them too much but my vision is just different and that's okay!

crossovers! while i'm so very happy dan schnider didn't have either of his disgusting hands in big time rush, i do remember watching the icarly/victorious crossover for the first time and wishing big time rush were there. it takes place in LA! the victorious kids are singers! carly, sam, and Freddie are pop culture experts! it would've worked really well :) so i'm writing that as a chapter for my fic LMAO

generally either an episode focusing in on or more scenes including james and lucy since the writers wanted them to be together so bad. inherently there's nothing wrong with them being together, but i do not think the relationship was given enough time to develop. give me lucy discovering her feelings for him, give me james not being creepy and obsessive about her; something more needed to be done on both of their parts to make me believe in it

additionally on that note more with jo/kendall and logan/camille; i love them both but they also had little development, just more than james/lucy. maybe they give carlos a gf (not alexa IMO, sorry. that got into weird territory for me idk why they made him be with a "real" person when he isn't other than they were already together irl) earlier and they can all have like conversations about their gfs and how much they love being together idk

and another generally, there were many songs btr put out that i love so much and feel like deserved their own episodes for hehe. i know not all of them have storylines easily transposed but i think they used confetti falling like four different times in the last season when any other love song from their third album could have been placed instead

and also another generally, and i know the early 2000s would've never allowed this for children's television but they should have and i'm the writer now!!!, but more representation all around. maybe some episodes about cultural heritage that didn't make stereotypes the main focus, canon LGBTQIA+ characters, holidays that aren't christmas, aspects like that where all kids can see themselves represented... LA is such a huge melting pot, it's not all white kids trying to make their dreams come true!

good god that was long SORRY AKJBSKJGBAB i have a lot to say and there's a lot im trying to incorporate into my story to add in what i think enhances the already present storyline. that's what's so beautiful about fandom, i love that we can have conversations like this :)

but what about you? anything you'd like to add in? i'd love to know <3 thank you for the question!

ask me a question! save my life!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Kevin Ray

Published: Jan 23, 2024

Prologue: Navigating Cultural Revolution

I’m days away from starting rehearsals for my third literary adaptation as a theater director; my heart is pounding with excitement and fear. There’s nothing more thrilling than the electricity of a vibrant rehearsal room full of talented, generous, creative actors and designers, collaborating with me to adapt literature into a play, but it’s also anxiety-producing because there are a million creative decisions to make. Nonetheless, the theater is booked and the curtain will rise in October 2024; the only thing to do is persist in the pursuit of making great theater.

The inspiration for this production—an adaptation of a 1924 dystopian novel by Russian heretic Yevgeny Zamyatin—arose from my experience, not in creative persistence, but persisting in the face of an ideology that endeavors to bar heretics like me from the arts.

A culture of the arts without heretics isn’t a healthy culture—it's a boring culture. Regrettably, a small but very loud group of activists in the theater have sidelined heretics by demanding artists conform to an identity-grievance fueled monoculture.

Fortunately, I found a way to make theater. I feared I’d be forced out of the field altogether. I lost work for refusing to promote concepts such as “White Supremacy Culture” and “Decolonization,” I infuriated some by refusing to adopt “gender-neutral pronouns,” and I faced disdain for being white, male, and even for identifying as gay and not “queer.”

Unfortunately, I was prepared to deal with identity-based discrimination—I’ve faced prejudice since the beginning of my career.

Act I: The Wrath of Westboro

I was drawn to theater from a young age, partly because theater groups were welcoming to oddballs, weirdos and outcasts who didn’t fit in elsewhere. Even before it was clear to me, my classmates knew I was gay, and I silently endured daily bullying. Theater was an oasis where I could get away from demeaning comments and fit in with other kids. I relished using my imagination to stand in the shoes of a character who was not me; facing obstacles in a different time and place.

By the late 1990’s I was acting, singing and dancing in a professional production of a musical that toured small and mid-sized cities across the United States. Getting paid to tour in that musical was the epitome of a “dream come true.”

I was lucky to be in that show for various reasons. First, the production held auditions in New York, a city overflowing with talented performers. Being cast in that show was, as they say, “a lucky break.” But this was not the first break I had had in my life.

When I was eight years old, I had a break of a different kind: I broke my neck. The two vertebrae just below my skull were fractured. A neurosurgeon told my mother and me it was rare to see someone with this injury still alive, most people died instantly; the few who lived were permanently paralyzed. After the neurosurgeon explained the procedure he would perform, he looked directly into my eyes and said, “If there is anything you want to do in your life, you should do it before this surgery.” I said I wanted to have another birthday.

I survived; and at twenty-six, I was dancing across stages around the country. More than lucky, that was miraculous.

The last bit of luck I had was the date of my birth. If I had been born a few years earlier, I may not have lived to see my twenty-sixth year. The generation of gay men who came just before me were ravaged by HIV/AIDS. As reported, “by 1995 one American gay man in nine was diagnosed with AIDS.” The epidemic also spawned an anti-gay activist movement.

Enter stage left: the Westboro Baptist Church. Founded by Fred Phelps in 1955, the church gained notoriety in the early 90’s for picketing a park frequented by gay men. As reported, they also “picketed at American soldiers’ funerals, thanking God for killing those who’d fought for a country that ‘institutionalized sin.’ They prayed God would kill Westboro’s enemies.” The musical I was in prominently featured gay male characters, making it a prime target for Westboro’s bigoted activism.

As our tour bus pulled into the parking lot of a Kansas theater, church members stood outside holding signs that read “God Hates Fags” and “Two Gay Rights: AIDS and Hell.” Many in the cast were gay, but to the Westboro protestors we were not three-dimensional human beings with the capacity to love, dream and hate, just like them. They didn’t care about the commitment we had to our craft, the challenges everyone overcame to be cast in the show, and that, at the end of the day, we were all performing in the musical because of our love for theater. The point of identity-grievance activism is to ignore our common humanity and weaponize identity.

The protesters were within their legal right to peacefully hold signs with heinous language. Considering the musical highlighted how difficult the lives of gay men can be because of the discrimination they face, I wonder if Westboro’s activism only deepened the meaning of our show: as they walked past the signs, that audience experienced, first-hand, the ignorant vitriol many gay men encounter.

I was afraid that night, but I did what I had to do: I went on with the show; Westboro didn’t stop me from living my dream.

Despite fringe groups like Westboro, the late 1990’s was a time of great advances for gay men. As the country headed toward a new century, society was becoming more welcoming to a wide variety of minority populations. How could any of us have predicted the identity-grievance nightmare that was to come, and the impact it would have on the theater?

Act II: A New Dream

When actors aren’t working in a show, they survive by holding down a “day job.” Around 2002, I stumbled into a day job as a Teaching Artist. Teaching Artists visit schools on behalf of cultural institutions (theaters, dance companies, orchestras etc.) delivering arts programming, often in under-funded districts that don’t have budgets to hire full-time arts teachers.

I didn’t think I would like teaching, but within a few months I was hooked. The students loved the opportunity to get out of their seats and participate in theater activities, and I was fascinated by the challenge of writing a lesson plan; it was like a magical chemistry experiment: two parts explaining directions, twenty parts playing games, one part classroom management. And it was a kind of performing, the curtain went up every time I entered a classroom.

I remember the exact moment I decided to stop pursuing acting. When I arrived at an elementary school in Far Rockaway, Queens for my third or fourth visit, I opened the door to the classroom, and the students exclaimed, “HE’S HERE!” At that moment I thought, “Nobody is excited when you walk into an audition room, but these kids, their teacher, and you are excited to be together in this classroom – go where it’s warm.”

I worked hard to improve my skills. I read books about teaching, went to conferences, and studied pedagogical theories. But the best way to learn how to teach, is to teach. So I took as many jobs as I could get, working with every age group from pre-K to high school, with students diagnosed with “special needs”, students who predominantly spoke Spanish and Polish, jobs in low-income neighborhoods and jobs at high-profile theaters offering programming for youth from wealthy families. I worked in schools, summer camps, and church basements. I loved theater, and I now loved teaching, which led me to a new dream: to become a theater professor.

In 2008, I enrolled in a graduate program without understanding all master’s degrees are not considered “terminal.” When I completed the program, I was devastated to discover my degree had no value in the academic job market. I sank into a deep clinical depression and spent the next year and a half digging myself out with the help of a skilled therapist. But in 2016, I had another lucky break: I was chosen for a Masters of Fine Arts (MFA) in Theater Directing. I earned my “terminal degree” in 2018. I was on my way to a successful career in academia, but a new kind of activism attempted to kill that dream.

Act III: Something Wicked This Way Comes

In the summer of 2018, I attended a national conference for theater professionals in higher education. A panelist with experience on hiring committees explained, “To teach theater and direct productions at a college or university, you have to have an MFA and you have to show the committee you can get yourself directing work at regional theaters.”

I left the panel deflated. During my final stretch of graduate school, we practiced “elevator pitches” for potential interviews with artistic directors. Although the professor said my pitch was excellent, I wondered, “Who would I pitch to? My chances of meeting with an artistic director are less than my chances of a sit down with the Pope!”

I knew this because an activist movement sometimes referred to as Critical Social Justice (CSJ) was deeply entrenched in the theater industry. In the same way Westboro Baptist Church demonized me based on an identity trait I could not change, CSJ activists in the theater were deciding who was a so-called “oppressor” based on identity. I was nearly everything they deemed “oppressive”: white, male, middle-aged and, probably worst of all, I identified as gay, not queer. For readers unfamiliar with the distinction, gay simply connotes same-sex sexual orientation while queer conjoins sexual orientation with a laundry list of radical leftist politics. Although many claim the word queer is “inclusive” of the variety of identities encapsulated in the ever-growing LGBTQIA+ acronym, as Andrew Sullivan explains, “queer” is “designed to trigger gay men, especially gay men who aren’t politically of the far left … to make us feel we aren’t part of the world or of the community.” Rather than function as a term of inclusivity, “queer” has been weaponized to identify and exclude traitors.

When I asked an aspiring playwright what she thought my chances were, she said white men had been directors “for so long” and it was time that they step aside. I didn’t think a person’s race or sex determined whether or not that person had the skills, talent or commitment to be a theater director.

Theater artists were the last people I suspected would attempt to bar anyone from participating in the arts based on identity. We were the oddballs, outcasts, and weirdos who accepted each other because our differences excluded us from mainstream culture. Now, my colleagues in the theater no longer saw me as a three-dimensional person with thoughts, feelings, and dreams untethered to my identity. Instead, I was nothing but an embodiment of identity characteristics they wanted to amputate.

I ran into a professor from my first stint in graduate school at a reception for theater directors in higher ed. Mid-conversation he said, “Look around this room! I’m the only person of color in here. I’m not feeling supported! Come with me.” Without telling me his intentions, he led me over to the event’s planner and told her the organization needed to do a better job getting “directors of color” into the room. I stood frozen, a dumbstruck pawn furthering someone else’s activist agenda.

I was used as a pawn again when I attended the second night of a festival of theater directors’ projects in development. The first two works came and went from the stage, but the third piece started on an odd note. A bald, middle-aged man stood center stage and a young female director sat far away from him on the stage’s edge. At first, I thought this was a curious experiment in hyper-realism, but I soon realized it was not a performance. The director apologized to the audience for the work presented the night before because, she said, she’d received several emails saying the piece “offended” and “harmed” some audience members. The man center stage chimed in, but was quickly cut off by the director who asserted, “I’m speaking now.” It was revealed the man was a former NYPD officer who asked the director to help adapt his experiences on the police force into a play. Suddenly, audience members who had been at the previous evening’s performance were standing and shouting at the retired officer. Each time he tried to defend himself, the director cut him off saying it was not his “time to speak.” The man’s wife stood up and pleaded, “My husband is a good man! He protected this city on 9/11!” But the ravenous audience continued to shred the retiree over the “offensive” and “harmful" words presented the night before, words we were now not allowed to hear. I never learned what the police officer said that caused this reaction. But from the way he was treated, it seemed his mere existence as a police officer was contrived as somehow “harmful" to these people—who wouldn’t even let him talk. After the “show” I approached the theater’s artistic director and said, “I didn't know I was going to be a participant in a public shaming before I bought a ticket to this event.” She said, “There were some things he needed to hear.”

On a cold January weekend in 2019, I was alone in my Brooklyn apartment desperately trying to hatch a plan to change my prospects in an ecosystem increasingly intolerant of people and views that did not conform to CSJ. To get a college teaching job, I needed to direct something. I decided I could either whine and cry that the activists were preventing me from realizing my dream, or I could create my own opportunity. If I couldn't direct a play at an established non-profit theater, maybe I could independently direct and produce it myself.

ACT IV: Burning Down the House

As part of my Teaching Artist work, I had experience “devising” original plays with youth. Devising is a theater-making technique that means collaboratively creating a play originating from an idea rather than a playwright’s pen. “Devisors” start with source material such as newspaper articles, transcripts of court documents, old photographs, paintings, stories, anything that stimulates ideas a devising ensemble can transform into a play. On that frigid weekend in 2019, I decided to devise a play from ghost stories by Edith Wharton. Best known for her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Age of Innocence (1920), Wharton skillfully used fiction to criticize rigid social structures and her lesser-known ghost stories overflow with rich social commentary and wry humor. I pitched the project to some colleagues from my MFA program. Excited both by the stories and my collaborative approach, they all said, “Yes!” They didn't see my identity as a liability, but my employers did.

In the fall of 2019, at an annual “back to school” workshop, I was, for the first time, segregated into what’s called a “racial affinity group.” When asked why we were breaking into groups by race, our supervisor said, “Because we live in a systemically racist country.” I was asked prior to the meeting via a Google survey if I was willing to participate in racially segregated groups, and I responded, “No.” After I was put in the “white affinity group,” I asked the facilitator why I had been segregated at work against my will. She told me she would get back to me. She never did.

At another arts organization, my supervisor called me into a private meeting to reprimand me for refusing to let my co-workers address me with “they/them” pronouns in emails. She said everyone was using “gender-neutral pronouns” in an organization-wide campaign to “dismantle patriarchal systems of oppression.” I let her know that I was a gay man, proud to be one, was not willing to let anyone else decide what my pronouns should be, and that applying pronouns to a person who doesn’t want them is the definition of “mis-gendering.” My supervisor bristled. I said, “Well then, we will have to agree to disagree.” In response, she slammed her hand on her desk, jumped out of her seat exclaiming, “NO!” and left the room. I wasn’t hired back.

I was also pressured to incorporate concepts from CSJ into my teaching. The idea was to “embed” theories such as Paulo Freire’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” Ibram X. Kendi’s “Anti-Racism,” Judith Butler’s “Queer Theory,” Frantz Fanon’s “Decolonization,” Kimberly Crenshaw’s “Intersectionality,” Robin DiAngelo’s “White Fragility,” and Tema Okun’s “White Supremacy Culture” into pre-K to 12 arts-instruction.

Instead of spreading the joy and excitement of theater, I was to use theater instruction as cover for indoctrinating children into a worldview that taught them to see themselves as victims or “oppressors” based on their race and sex. When I voiced concerns, I wasn’t offered further work.

Determined to “dismantle” so-called “harmful white-centered” practices in the theater, activists were inadvertently destroying collaboration. The most important ingredient in collaboration is trust. Trust enables collaborators to bravely take artistic risks as an ensemble. But the activists were sowing distrust by reducing everyone to identities “oppressing” each other; re-casting benign interactions as overt acts of prejudice or covert insults like “white women’s tears” and “microaggressions”—the latter is a doctrine that turns everyday interactions, like asking where someone is from, into a grave racial insult if a listener decides their subjective feelings are hurt. Where there are no real insults or real acts of aggression, “microaggressions” can be manufactured out of thin air. Rehearsal rooms became ticking time bombs where activist artists could hurl overblown accusations of supposed psychic harm at any moment.

Not satisfied with obliterating collaboration, the activists jettisoned their audience. As reported in Washingtonian, when a theater endeavored to revamp its programming to create “the most woke theater in Washington,” the journalist wondered, “Can they do this without alienating a crowd who, liberal as they may be, might also be slower to get with the times?” To which an executive board member replied, “It’s entirely likely that as we continue the work we’re doing, we’re going to lose more people, and I think we’re all okay with that.”

I attended one show that ended by pressuring “the folks who call themselves white” to leave their seats and stand on stage to understand that they don’t “own” their seats. At another show, “non-Black audience members were invited to leave” before the end because the play was “not for or about” them. Some productions held segregated “black out” performances. How do you reach hearts and minds when you’re kicking hearts and minds out of the space?

When the pandemic hit, and all our work meetings took place on Zoom, I repeatedly heard the phrase “burn it all down” from my Millennial and Gen Z colleagues. Their perspective seemed to be the theater that existed before the lockdown was a racist, sexist, misogynist, homophobic, transphobic, xenophobic, capitalist (fill in whatever “-ists” and “-phobics” you could think of) oppressive system of “predominately white institutions” traumatizing artists through a “nonprofit industrial complex” (an oxymoron in any case) that needed to be vaporized. As reported in The Intercept, Millennial and Gen Z employees across the nonprofit sector were, in the words of one anonymous senior leader, “not doing well” and creating a “toxic dynamic of whatever you want to call it - callout culture, cancel culture whatever - [that’s] creating this really intense thing, and no one is able to acknowledge it, no one's able to talk about it, no one's able to say how bad it is.” It should have come as a surprise to no one that, during 2020’s summer of “fiery but mostly peaceful” protests, the atmosphere imploded.

First came the "Not Speaking Out” list, a Google spreadsheet listing the names of not-for-profit theaters that did not make a “sufficient” statement on social media about “systemic racism.” Then came “We See You White American Theater,” a twenty-nine page list of demands for reform that included race-based hiring quotas, ceasing “all contractual security agreements with police departments,” and requiring “creative teams to undergo Anti-Racism Workshops at the beginning of each rehearsal or tech process and ensure accountability with signed statements.” Finally came the targeted attacks on non-compliant individuals. One of the most heartbreaking incidents was the pressure campaign that preceded an executive director’s resignation. Her own staff circulated an online petition to the entire membership stating:

We are here to tell you that, underneath your dress of respectability politics, your slip is showing… it looks like your predatory tokenism of BIPOC staff members, your opportunistic fundraising, and your calculated obstruction of anti-racist programming.

This executive director played a major role in sustaining not-for-profit theater in New York City through the aftermath of 9/11 and "The Great Recession” of 2007-08 and was an ardent advocate for promoting women as leaders in the field. But the petition painted her as a notorious racist who needed to be excommunicated. I was horrified to see the document populated with the names of people I’d known for years. I declined to sign. No one publicly came to this woman's defense because the activists’ tactic was clear: do what we say, or we will cull you from the field too.

Overt discrimination permeated every meeting I attended that summer. At an organization established to support theater directors, one member asked the group’s president, “Can we have a conversation at some point about the ethics of white directors?” When asked for clarification, the member said, “This is about the ethical responsibilities of white… members as we work to transform the American theater… and whether white directors should be directing.” The president responded, “We’ve already begun to put a task force together… to help particularly our white members work through setting up rehearsal halls and production processes that are anti-racist.” It was odd that only white directors were singled out as needing support understanding what is or isn't “anti-racist” because, from what I saw, there was a lot of racial discrimination aimed at white people.

A prime example was American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter Keith Wann, who lost work solely based on his skin color. As New York Post reported, the director of ASL for Broadway’s The Lion King stated, “Keith Wann, though an amazing ASL performer, is not a black person and therefore should not be representing Lion King.” To be clear, and typical of the convoluted logic of this movement, the director was advancing the proposition that only black ASL performers should play the animal characters in The Lion King. Since when was it “anti-racist” to insist that only black people were uniquely fit to play animals? Citing race-based employment discrimination, Wann sued. According to court documents, the case settled in Wann’s favor with lightning speed. Perhaps this employer should have provided staff with “anti-racist” training that included Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John G. Roberts and his plurality opinion in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School Dist. No. 1, which states, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

Activists pressured artists to create theater aligned with their beliefs. As reported in The New York Times, the artistic director of a festival that once prided itself on being “uncensored” canceled a show because the playwright and performer dared to assert, “There are two sexes, male and female.” The artistic director explained, “I support free speech, I think all speech should be legally protected, but not all speech should be platformed.” Jonathan Rauch, Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institute, explains the motivation behind this type of behavior in his book Kindly Inquisitors, “In an orthodox community, the threat of social disintegration is never further away than the first dissenter. So the community joins together to stigmatize dissent.” Stigmatizing unorthodox views by canceling shows that express them is censorship, and theater artists used to know better: In 1992, Stephen Sondheim refused the National Medal of Arts award from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), stating it would “be an act of the utmost hypocrisy” to accept the award because the NEA had become “a conduit and a symbol of censorship and repression rather than encouragement and support.”

Unlike film, television and recorded music, live theater has no rating system; it should not look for ways to self-censor. Not only should theater reject self-censorship, it should overflow with a wide variety of plays that explore uncharted, daring and dangerous topics. Why not unleash diverse perspectives on various stages and let audiences decide what they think? Instead, activists insist the theater should be comprised of people who, however much they all may look different superficially, must all share the same beliefs. That’s not diversity, it’s monoculture.

If some artists want to create shows that extol CSJ, they have every right to pursue their projects. However, they have no right to bar other artists from daring to critique CSJ’s inconsistencies and intolerance.

Westboro knew they could hold slanderous signs, but they understood attempting to stop the show was beyond their purview–it’s time CSJ activists in the arts learned that lesson.

A few voices of dissent have begun to document the devastation caused by this activism as Clayton Fox does in his essay “The Toxic Gentleness of the American Theater”, but a New York Times article titled “A Crisis in America’s Theaters Leaves Prestigious Stages Dark” hints insiders know some of this “crisis” was self-inflicted. As an executive director admits, “Some theaters have forgotten what audiences want — they want to laugh and to be joyful and to cry, but sometimes we push them too far.”

ACT V: Building New Institutions

At the risk of being the skunk at the garden party, I don't believe logic and reason can be used to persuade theater leaders to take an off-ramp from their misguided allegiance to CSJ. Their devotion is fundamentalist in nature, and that is nearly impossible to pierce by persuasion, even if someone could get them to listen in good faith.

Look at the example of former Westboro member Megan Phelps-Roper: it took thirteen years of engaging with opposing views before she left the church. At fifty-one, I can’t wait for people to change their minds before I make art. The way to make art now is to build new institutions that state from inception a commitment to freedom of artistic expression, a recognition that ideological conformity is not a prerequisite for participation in the arts, and a pledge to refrain from making statements on social media about current events. If theaters want to tackle current events, do it on the stage.

Despite the storm around me, I pursued my ghost story project. I needed funding, so I looked for grant opportunities. One application asked, “Why this project, why now?” I wrote that a project based on ghost stories was relevant to the moment because they are about our relationship to transgressions in the past. Every ghost story features the living encountering an apparition who returns either to make the protagonist aware of a past injustice, or to punish the protagonist in the present. Considering Ibram X. Kendi declared in How to Be an Anti-Racist, “the only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination,” I thought it would be meaningful for audiences to experience what happens when people are punished for things in the past, whether they had anything to do with the earlier transgression or not.

It worked! In 2021 I received two small grants to produce and direct Unearthly Visitants. The project went so well that my collaborators and I decided to mount a second show, an adaptation of E.M. Forster's 1909 science fiction story "The Machine Stops." In a review, a critic wrote the play was "a Space Mountain roller coaster ride, an intellectual white water rafting expedition, a production that will have you talking about it for hours and days to come.”

Every moment putting those shows together was pure joy and fulfillment. I didn’t “embed” CSJ into the rehearsal room or the plays. I didn’t force the ensemble to declare preferred gender pronouns, no one was accused of “microaggressions,” and I didn’t impose my socio-political beliefs onto anyone else. The rehearsals were about the bliss of creating the best productions we could devise.

Identity is important. I don't deny that. My identity surely informs my views, but it is not the totality of who I am. Reducing everyone to the same person based on identities serves activists’ causes, but we are simply not all the same.

Artists have choices: they can use identity to blame, shame and divide, or they can use identity to bring people together, helping us see what we have in common, despite our differences. Most new theater I've seen that wades into identity expresses a contradiction that linguistics professor and New York Times columnist John McWhorter identifies in Woke Racism: “You must strive eternally to understand the experiences of black people,” while simultaneously insisting, “You can never understand what it is to be black, and if you think you do you’re a racist.” McWhorter discusses only race, but the contradiction he pinpoints has been applied to various “oppressed” identities in several plays. This fashion is wearing itself out, but I fear it will leave behind a long-lasting stain of resentment, assuming an audience remains in its aftermath.

One of the four Wharton ghost stories I chose to include in Unearthly Visitants, “The Eyes,” featured a main character Wharton strongly suggests is homosexual. The story shows the cost he pays for not accepting himself. Anyone can identify with struggling for self-acceptance. Wharton didn’t wield homosexuality as a weapon to berate and alienate, she used it as a window to let readers experience the price paid for refusing to accept oneself. Theater should offer audiences more windows, and fewer mirrors merely reflecting back every audience member's identity.

Being an independent producer and director is hard, but rewarding. I choose who I work with, what we work on, and how we collaborate. It’s a lot of responsibility, but when things go right it feels great. It’s not what I imagined I’d be doing in my fifties, yet here I am, putting together my third production: an adaptation of Russian dissident Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1924 dystopian novel We. Zamyatin is a true hero: a Bolshevik who left the party when it declared “all art must be useful to the movement,” he spoke out against party orthodoxy when doing so had mortal consequences. In his 1921 essay “I Am Afraid,” Zamyatin wrote,

“True literature can exist only where it is created, not by diligent and trustworthy functionaries, but by madmen, hermits, heretics, dreamers, rebels, and skeptics.” The same could be said of “true theater.”

I owe both the Westboro Baptist Church and Critical Social Justice activists heartfelt gratitude because their efforts backfired: instead of culling a gay, white, middle-aged artist from the field, they created a resourceful, resilient and persistent artist, committed to freedom of expression, fairness, a belief in common humanity, and hellbent on finding joy and fulfillment as a theater director – isn’t that a great thing.

And I haven’t given up my dream of getting a college or university teaching job. As the saying goes, “Don’t quit before the miracle.”

Epilogue: Calls to Action

Essays like this can make readers feel overwhelmed because things aren’t changing fast enough. Fear not–there are things you can do to help:

Like and follow artists whose work you support on social media;

Subscribe to Substacks and alternative publishing outlets like this one;

Write a letter to your local theater. If you see a show you liked, let them know. If they put on lousy shows, write a letter telling them you didn’t like what you saw and why;

Don’t give money to theatrical institutions putting on shallow morality plays. Instead, give money to organizations you like. Send a letter explaining why you didn’t contribute to the former’s annual fundraiser and why you did to the latter;

Keep in mind the saying, “Politics is downstream of culture.” If you care about the future of our country, get involved in the arts.

==

“I didn't know I was going to be a participant in a public shaming before I bought a ticket to this event.”

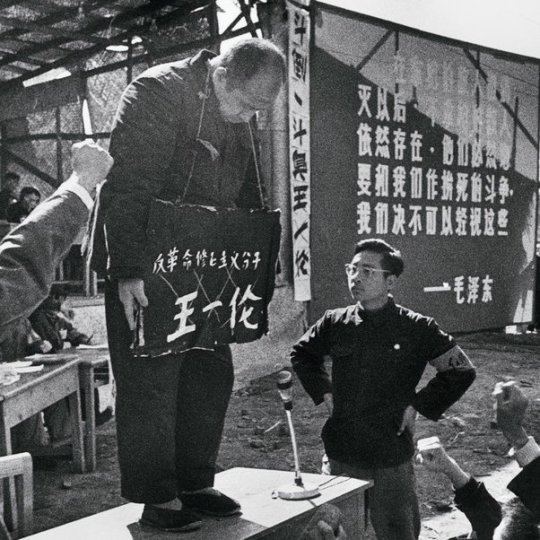

This is literally what they did in China. It's called a struggle session.

#We The Black Sheep#Kevin Ray#corruption of arts#the arts#social justice activism#critical social justice#ideological conformity#ideological capture#ideological corruption#Westboro Baptist Church#racial discrimination#woke racism#wokeness#woke#cult of woke#wokeism#wokeness as religion#politics is downstream of culture#religion is a mental illness

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

human aus of tvc are so much fun idk why people don't write them more often! i've had this plot bunny of l/a living in a ramshackle paris apartm. armand lives above lestat and he has this ruggish bf (santino?) and the guy isn't scared of armand's friend/neighbor bc he's never seen him & only heard he's gay, blonde and a ballet dancer so absolutely no threat right? Well SIKE bc one time he yells armand a lil too loud & suddenly his door is kicked open and a blonde beefcake has him in a chokehold

I actually think about the why part of this question a lot, because (obviously) I love a good AU! In my opinion, it's because of our fandom's very complicated history with fic that has continued to influence VC creator culture today. I think a lot of people do want to be creative and experiment, but (and maybe it's just me, I don't know) I get the feeling like collectively there's this sense of waiting for someone else to do it first that will indicate it's acceptable to play outside of the box.

Whether it's beyond writing the juggernaut ships (Loustat and Devil's Minion) or exploring kinks (this is a very kinky series, people!) or the endless possibilities of AUs, there's a certain audience for everything and I find people do respond pretty well to something different! It's always with a sense of surprise too, which I find funny and interesting and little sad, because it's nothing that you'd be batting an eye at in most other fandoms from what I can tell.

But because we're a fandom that only recently has started writing fic in the open (recently in comparison to our almost 40 years of existing), I feel like we're only just now starting to be that much more adventurous in a sense. You can talk openly, exchange content openly, it's a very different landscape than it was before. So I'm excited to see what the VC fic offerings will look like in a year or five years from now—it feels promising!

I got carried away lmao I HAVE THOUGHTS, but let's talk about this plot bunny. I just have to say... the image of Lestat kicking down Santino's door like the Big Bird gif laid me the fuck out. Anon, PLEASE. 😭 (Also not a bad analogy for how he came barging into Armand's cemetery self-imposed cell, from Armand's POV).

It's very sweet to think about Armand and Lestat starting off as friends! I always imagine that Amadeo and mortal!Lestat would've gotten along beautifully (they would have both fallen into the canal lbr). And Lestat's so protective of him in canon, it translates well. 🥹

Of course, Armand isn't going to tell his abusive boyfriend much about his friends and what he does when he's on his own. For a bit of a darker theme... maybe Santino's also his pimp? Armand doesn't tell Lestat any of this, he's too ashamed and hates appearing weak, and he just wants to forget his problems in the few moments where they can hang out on the front steps and share a snack and a cigarette. And Lestat might have his head in the clouds sometimes, but he's not stupid. He hears things, sees how Armand shrinks into himself and ignores him completely if Santino's around, won't speak unless told to, etc.

Lestat's young though, and not thinking how he might be worsening the situation by acting so rashly. Even though Armand's going to be grateful later, he's horrified in the moment knowing that Lestat's just made himself a target of Santino's gang in the future. And that Santino is going to think Armand's been running his mouth to Lestat and he or one of his buddies be taking it out on Armand the first chance they get.

Insert lots of drama, hurt/comfort, sex... Lestat and Armand eventually run away together and start over in New York City. Similar crappy apartment, only they're safe and together, and they live HEA.

~ fin

#this was a smorgasbord of a post#fandom thoughts#au thoughts#armand/lestat#vc#you ask and hekate answers

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

A and M for the end of year writing asks please

End of the Year Writing Meme!

A. If you could rec a piece of music to accompany one of your fics, what would you pick? Why?

This is a little cheesy but I feel like Hailee Steinfeld - Most Girls would be really nice with Shiny Rainbow Knife, since it's very much "fuck yeah, you're a girl, and you're awesome."

M. Meta! Have any meta about a story you’re dying to throw out there?

I feel like I've shared most of the meta for things I've written already??? Uhhhhhh okay, got one.

The Making of Mand'alor Kryze has a lot of question for 'how do we have this diaspora child remain connected to his mother's culture now that she's dead?' Obi-Wan goes for the equivalent of Sunday School, searching for a religious center that doubles as community center. The meta/lore part is actually that this is directly influenced by my experience as an immigrant and part of the Serbian diaspora of the 1990s.

I moved around a lot as a child, but I spent a huge chunk of it in the outer boroughs of NYC, and later Long Island. In that time, we went to the Saint Sava Church of New York City (Trinity Chapel Complex), first somewhat regularly, but later only a few times a year, due to it being several hours away depending on traffic. I don't remember a whole lot of theology or scripture. What I do remember, though, is that after a service, we would all filter out into the adjacent building, where there was food, holiday parties, a few pianos, sometimes poetry readings. For all that religion isn't a part of my life, I associate a lot of cultural memories with that church because it was one of the only places I could reliably see other members of the diaspora that weren't just my parents immediate friends.

(I did do Sunday School, actually. I got pulled from it for, among other things, asking too many questions.)

So in my eyes, a 'cultural center' is often specifically the religious center, and then things branch out from there. If you aren't a particularly large minority population, you don't get secular spaces other than a few restaurants. But you do, probably, have a church.

(Or used to. Saint Sava Church of NYC burned down in 2016 for reasons that are officially a mistake with the candles, but widely suspected to be arson. They're still working on building up the funds to rebuild.)

Now, the actual application to the story is different, because Korkie is more religious than I am, and there actually is a sizeable Mandalorian community, such that they can have their own neighborhood. It is, however, a good starting point for Korkie to connect with the nearest Mandalorians, and I'm imagining that Obi-Wan is a bit more invested in ensuring Korkie does know Satine's religion as a faith, not just in theory.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Atlantic: Are You Plagued by the Feeling That Everyone Used to Be Nicer?

I have a long-running argument with my brother. He insists that his children, who are growing up in New York City right now, are a lot less safe than we were as kids in the same neighborhood. I happen to know this is absurd, and I’ve tried for many years to convince him. I’ve shown him news reports, crime statistics. Once I even downloaded an FBI report showing without a doubt that New York was much more dangerous 30 years ago. But he is unmoved. He remembers our childhood as gentler, safer. And I have to admit—there are moments when I walk around my old neighborhood and see visions of the mailman tipping his hat to my 10-year-old self, and the neighbors smiling as I made my way home to dinner.

Why do so many of us have this feeling that when we were younger, people were nicer and more moral, and took care of one another better? An experimental psychologist named Adam Mastroianni had also been wondering about this persistent conviction and did a systematic study of the phenomenon recently published in Nature.

Mastroianni documents that this hazy memory is shared by many different demographics, and felt quite strongly. He explains how the illusion works and why it has such a hold on us. And most important, he explains how it can distort not just our personal relationships but our culture and politics. In this episode of Radio Atlantic, I talk with Mastroianni and staff writer Julie Beck about the illusion of moral decline, and why it persists so strongly.

Whenever politicians or aspiring politicians make the claim that, you know, “Things used to be better, put me in charge and I’ll make them better again”—that’s a very old thing that we’ve heard many times. And it resonates with us, perhaps because we are primed to believe it, even when it’s not true.

The following episode transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Hanna Rosin: So, Julie, you know—even though I get annoyed when other people say people used to be nicer, I kind of think I might feel that way too.

If I have a vision of my childhood and I’m walking down the street from the playground, I imagine all my neighbors saying, “Hi, little Hanna.” [Laughter.] And the mailman coming by, you know, and tipping his hat at me, and the old man walking his dog.

And, you know, I have no idea if this memory is accurate, but I definitely have that feeling that people were nicer.

Julie Beck: Did you grow up in Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood? Or what was it?

Rosin: No; I actually grew up in Queens, New York. So it’s probably, certainly not true. [Laughter.]

This is Radio Atlantic. I’m Hanna Rosin. I invited my colleague Julie Beck on to talk about something that’s always really bothered me. It’s when people talk about how things are so much worse today than they were in the past.

And they say things like “Neighbors used to be nicer, and everyone used to smile at you and help you out.” And sometimes it’s just grandpa chatter and you can pretty much ignore it. And then other times it turns into this “back when men were men and women were women”–type thing, which is more annoying.

Beck: There’s a benign wish to, like, tip your hat to the mailman. And then there’s a “Oh, we need to bring back the social order of the 1950s.” And then you’re like, “Whoa, how did we end up here?”

Julie analyzes psychological research and social trends, and she’s also the host of another Atlantic podcast, How to Talk to People.

And she’s here to help me understand this very interesting research that just emerged about this strong conviction people have that everything has gotten worse.

Adam Mastroianni: So my whole life, I’ve heard people say things like, “You used to be able to keep your doors unlocked at night,” or “You can’t trust someone’s word anymore.”

And I always chafed at those kinds of statements. So part of it was wanting to prove everybody wrong. But part of it, too, was like, Well, if they’re right, this is a big problem. And that’s kind of where we got started.

Rosin: That is Adam Mastroianni. He recently published a paper in Nature called “The Illusion of Moral Decline.” Adam is a psychologist, and he’s the author of the science blog Experimental History. And he spent a decade systematically studying why we feel things were better in the past … and what it means.

Mastroianni: I think my first year of graduate school was when Trump got elected. And so obviously it was a moment of “Make America Great Again” being sort of the vibe of the day.

Seeing claims that “The past was good, the present is bad, put me in charge and I can bring the good past back” also just made me see how this is much more than, you know, uncles and brothers-in-law and people on the internet saying these things— that these claims resonate with people, and they help put people in the Oval Office.

Rosin: Yeah. I mean, I have to say, that’s my motivation for being interested in your research, because I have always had a kind of detached curiosity about why this line resonates so strongly.

Like, why is it that—and it’s not just American leaders, it’s leaders all over the world—they can just say, “Oh, things were better back then,” and it immediately clicks for people? Like, they don’t even have to explain it. You can just say, “You know, make America great again.” It’s like four words, and all the assumptions are immediately there for people.

Mastroianni: Yeah. When I give talks in an academic context about this paper, what I start with is the end of Trump’s inaugural speech, where he says, “You know, we’ll make America wealthy again and proud again and safe again and great again.” And I point out that the most important word in those sentences isn’t America or safe or proud or strong or great. It’s again.

Rosin: Yes!

Mastroianni: Just that word does a ton of work. Which is that: Well, if things used to be great but aren’t now, it means something changed. It implies that we can change it back. It evokes a sense of loss, but also a sense of possibility of restoring the loss.

Rosin: Yeah. And it is the word again. It’s like that one little word sort of resolves something emotionally for people. It’s hard to understand exactly how it works, but you say the word again, and everyone’s like, “Ah, you just filled a hole for me.” You know? What exactly do you mean when you say “moral decline,” and why, if it’s an illusion, does it feel so real?

Mastroianni: There are a few totally reasonable hypotheses about what people might think of when they talk about moral decline. It might be that everyone means, like, “I heard that the 1950s were a really good time. And so what I’m really telling you is things have declined since then.” Not that they got worse in the past 10 years; that they got worse, you know, 20 years ago or 50 years ago. And we’re just living in the bad times now.

In a later study, we asked people go back even further than that. “What about 20 years before that? What about 40 years before that?” And what they told us there is—“Before I arrived, nothing was happening. Things were good. Then I got born, and then things started to go downhill.”

And what’s especially interesting is: It doesn’t matter when you were born. So the people who were 30 told us it happened 30 years ago. The people who were 60 told us it happened 60 years ago.

Rosin: Wait, really? So literally, people think the decline began when they came on this earth?

Mastroianni: Yeah. So, I mean, we don’t ask, like, the day before or the day after. But the question that we asked was: “Rate how kind, honest, nice, and good people are today. What about the year in which you were 20?” And people told us it was better then.

“What about the year in which you were born?” And people told us it was even better then. And then we asked, “What about 20 years before that? And 40 years before that?”

And there’s no difference in people’s answers. That line is flat. It’s only when we asked about “20 years after your birth” that the line goes down.

Rosin: That is so interesting. I don’t think I fully grasped that. So people are projecting whatever personal difficulties or struggles of life—now maybe I’m extrapolating—onto the whole of humanity, like they’re protecting their own life span onto a historical, broader cultural, political life span.

Mastroianni: Yeah. And I mean, this is a bias of people’s memory, because you don’t have memories from before you were born. You do have memories from most of the time after you were born.

So it would make sense—if this is a memory bias—that it turns on sometime near the moment of your birth. Obviously not exactly then, but this would explain why we don’t see this for what people think about before they were born and after.

Rosin: Does it really not matter how young you are? The stereotype is obviously, you know, Grandpa Simpson. It’s like, older people are always talking about how things were better back then, but not necessarily younger people.

Mastroianni: Yeah; we totally expected to find that as well, and we didn’t really. So when you ask people about the decline that they have perceived over their lifetimes, there’s no difference in the decline that younger and older people perceive.

Rosin: Julie, I was surprised to hear that there wasn’t a difference between older people and younger people in terms of how they perceive this moral decline. I mean, you’re not an old person; you’re young. So do you remember ever having this feeling?

Beck: I distinctly remember I did not get a smartphone until I moved to D.C. in 2013. So in the years before that, when I lived in Chicago, I have a memory of having so many more interactions with strangers on the street.

And I definitely do not have those nearly as frequently anymore. And I think it’s just because we’re all looking at our phones, right? So part of me kind of romanticizes the, you know, chance encounters of the pre-smartphone era and all of that.

Rosin: Yeah. And when I hear you say that, I’m like, Oh, it’s fine for Julie to have that feeling, and it’s fine for me to have that feeling. But if I multiply it by a few million times, then I get this political movement of “Let’s go back to the era when things were better,” and that I don’t really like so much.

Beck: Yeah. One thing that this makes me think of, too, is a line of research that has found that social trust has actually been declining in the U.S. for decades. So people are essentially less and less likely to say that generally most other people can be trusted.

And so you’re totally right that there are really big political implications for thinking the past was better and people used to be more trustworthy.

For me, it feels like kind of a chicken-or-an-egg question. Like, do we trust people less because we believe they’ve gotten morally worse? Or do we believe people are worse because we’re more disconnected from our communities?

Mastroianni: We focused here on a pretty narrow question, which is, “Has the way that people treat one another in their everyday lives changed over time?” And do people think that it has?

This is a model of when things are bad, it’s easy for them to seem like they have gotten worse. And so I don’t think this is the only domain where we might find this illusion, because people say this about a lot of different parts of life.

You know: that art is worse than it used to be. That culture is worse than it used to be. That the education system is worse than it used to be. But it seems pretty clear to me that we are predisposed to believe that it’s true, even when it’s not.

Rosin: Your assumptions in this research are—people have this idea that a certain kind of morality has declined. But in your mind, it has not declined. So to you, this is like an illusion. I mean, you call it an illusion. Right?

Mastroianni: Yes.

Rosin: Okay. So working within that assumption, what’s your explanation? Like, why would a majority of us be operating under a delusion/illusion? Like something that you’re saying is clearly not true.

Mastroianni: We think that there are two cognitive biases that can combine to produce this illusion. So this explanation has two parts. The first is what we call biased exposure, which is that people tend to attend to predominantly negative information, especially about people that they don’t know.

So this is both a combination of the information that they receive about people that they don’t know, which is primarily negative, and the information that they pay attention to. So this is why when you look out at the world beyond your personal world, it looks like it’s full of people who are doing bad things. They’re lying and cheating and stealing and killing.

The second part of the explanation is what we call biased memory. Memory researchers have noticed that the badness of bad memories tends to fade faster than the goodness of good memories.

So if you got turned down for your high-school prom, it feels pretty bad at the time. Twenty years later, it’s maybe a funny story. If you have a great high-school prom, it feels pretty good at the time. And 20 years later, it’s still a pretty nice memory. It doesn’t feel as nice as it did to experience it, but it still feels pretty nice.

And that turns out to be, on average, what happens to people’s memories: that the bad ones inch toward neutral faster than the good ones do, And the bad ones are more likely to both be forgotten and to become good in retrospect.

Beck: So when I read the paper, Hanna, I wondered whether what might be going on is that people are, to some degree, picking up on a real change in the world.

There’s the decline of social trust—but also widespread loneliness and disconnection and the erosion of community life, in the sense of fewer people knowing their neighbors and declining membership in community organizations.

And all of those things definitely have an impact on people’s personal lives. But I think it manifests as a vague feeling like, Oh, it’s just harder to make friends or harder to feel like I’m a part of my community.

So I wonder if we’re feeling this sort of vague and troubling sense of disconnection and assigning it a false explanation: that things used to be better before, and people just suck more than they used to.

Rosin: Oh, that’s really interesting. So what you’re saying is the feeling is real. Like, the feeling that something has changed is real because something has changed. There is more disconnection and loneliness.

So instead we make up this very tidy story. Like, “When I was a kid, things were better and people were nicer and the mailman tipped his hat”—and we just kind of stopped there.

Beck: Yeah; there definitely are real things that are really happening that would make people feel disconnected from strangers around them. And I wonder if, yeah, we just have a hard time psychologically, knowing why that’s the case.

Rosin: So Adam, I want to run a couple of theories by you. One is the possibility that something has actually changed. And we’re just calling it by the wrong name. That, like, something has declined. And this is from a different body of psychological research about social trust.

That there is a change in our isolation, our sense of connectedness, our face-to-ace contact. Like there are some societal changes which are real and structural and have kind of left a hole in us that we are misnaming morality.

When we read it here, we thought there are some things that are changing and that do leave us a little despairing—and maybe we’re just calling them by the wrong name.

Mastroianni: Yeah.

Rosin: Like we have this incredibly powerful feeling that something is wrong, and that “something” is connectedness or community or something like that.

Mastroianni: Yeah. So it’s very easy to slip from “People are less kind than they used to be” to “Things are worse than they used to be.” And so it is true that trust in institutions has declined over time. A lot of people also say that interpersonal trust has declined over time. And I actually think that case is much more overstated than the decline in institutional trust.

There’s some work by a guy named Richard Eibach on how people think the world has gotten more dangerous. And he finds that people believe this. And the people who believe this, especially, are parents. And when you ask those parents “When did the world become more dangerous?,” you get a date that is curiously close to the date of the birth of their first child.

The obvious implication being that nothing about the world changed. It was your worldview that changed. And now you have to, you know, protect this fragile life—and so you are much more attuned to the dangers of the world. That’s why you think there’s more of them.

Rosin: You know, Julie, I have this conversation with my brother all the time, and he’s always telling me his kids aren’t safe. He lives in New York. He’s like, “My kids aren’t safe. They can’t go outside. They can’t go down the block.” Like, he really freaks out, you know? And: “It’s way less safe than it was when we were kids.” And I’m like, “Dude, we grew up in New York in the ’70s, right?” It was really not safe.

Beck: Like, statistically.

Rosin: Statistically. And I’ve shown him news articles, and I once pulled out an FBI report. I specially downloaded an FBI report that showed, you know, crime statistics in New York from when we were kids.

And his conviction is so strong about this. I can’t budge him. I can’t show him enough numbers or statistics to make him think, Oh, things aren’t worse now.

I mean, Adam Mastroianni actually has a term for this. This is a little mean to my brother, but his term is unearned conviction. And I think what he means by that is exactly this. It’s like: Your conviction is incredibly strong, even though you have really no basis to back up the story that you’re attaching to that very strong conviction.

Beck: Yeah. I mean it seems like, regardless of the FBI report, the story your brother is telling himself is super-emotionally resonant.

Rosin: Yes.

Beck: And the stories that we tell ourselves about our own lives really do sort of shape who we are. It’s really interesting, because when we tell these stories to ourselves about our personal lives, a lot of times those stories fall into one of two categories. One being redemptive and the other being contamination.

And so a redemptive story is like: “I have suffered through these trials and come out stronger for it, and things are looking up.” Whereas a contamination story is like: “These trials have conquered me, and I am now broken and fundamentally a worse person.”